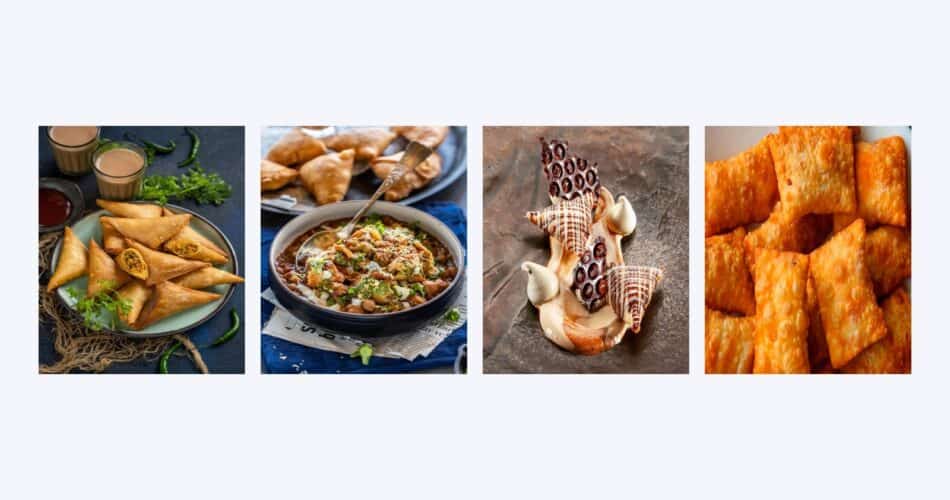

When Akshay Kumar was declaring his love for Juhi Chawla in the 1997 romantic comedy film ‘Mr and Mrs Khiladi’ with the famously corny line, ‘Jab Tak Rahega Samose Mein Alu, Tera Rahunga O Meri Shalu’ (As long as there are potatoes in samosas, I will remain yours, O Shalu!), his on-screen character was also immortalising India’s long romance with its favourite savoury tea-time snack also known as ‘shingara’ in the eastern states and ‘lukmi’ in Hyderabad. And the World Samosa Day, celebrated each year on September 5, is a tribute to this abiding love.

Historical references to the samosa (then known as ‘sambusak’ or ‘sambsag’, as named in medieval Arab cookbooks) go back to the oft-quoted riddle attributed to Amir Khusrau (1253-1325), the Sufi poet, polymath and spiritual disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi. Playing on the word ‘talaa’, which means ‘fried’ and also ‘shoe sole’, the riddler asks: “Samosa kyun na khaya? Joota kyun na pehna? Talaa na tha.” [Translation: Why wasn’t the samosa eaten? Why wasn’t the shoe worn? It was not fried/the shoe did not have a sole.] If the ‘samosa’ could make its way into a popular riddle dating back to the 13th-14th centuries, despite its Central Asian/Middle Eastern origins, t was obviously not just an indulgence of the royalty.

In the only detailed account we have of a royal meal served when the Delhi Sultanate held sway over northern India, Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta (1304-1368/69), a jurist from Tangiers, Morocco, who set a contemporary record in world travel, crisscrossing 40 nations and 120,000 kilometres between 1325 and 1354, notes being served ‘sambusak’, among the many other savoury and sweet items, which he describes as triangular pastries made of pieces of thin bread that are folded to pack in “hashed meat” cooked with almonds, walnuts, pistachios, onions and spices, and then fried in ghee. His host was the eccentric and erratic Delhi Sultan, Mohammad bin Tughlaq, then believed to be the richest ruler in the world.

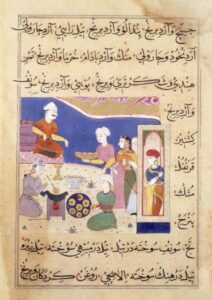

As many as eight different recipes for samosas (none with potatoes, because the tuber hadn’t yet made its way into the Indian diet – it happened only in the mid- to late 19th century) appear in the richly illustrated Indo-Persian cookbook titled ‘Nimatnamah Naṣir al-Din Shahi’ (Naṣir al-Din Shah’s Book of Delicacies). It was originally written by the pleasure-seeking Ghiyath Shah (r. 1469 to 1500), a ruler of the Malwa Sultanate based out of Mandu in central India, and completed by his son Abd al-Muzaffar Nasir Shah (r. 1500 to 1510). The manuscript, now in the India Office collections of the British Library, London, drew the attention of culinary historians after it was translated by Norah M. Titley in 2005.

The samosas described in the ‘Nimatnamah’ had what may seem like unusual fillings today: deer and mountain sheep meat; ground wheat cooked in ghee; dried whole milk (khoya) flavoured with spices and rose water; and sweet spiced cream and coconut. Even Abul Fazl’s classic description of India at the time of Emperor Akbar, ‘Ain-i-Akbari’, mentions the ‘qutab’, “which the people of Hindustan call ‘sanbusah’.” The ingredients include meat, flour, ghee, onions, fresh ginger, and a spice mix of pepper, coriander seeds, cardamom, cumin seeds, cloves and sumac. “This can be cooked in 20 different ways and gives four full servings,” the author notes. In fact, the quantities listed with each ingredient seem to indicate that the recipe was for a royal feast.

So, if people today are selling samosas packed with chowmein, or with cream and corn or onions, or dishing up ‘pizza samosas’ loaded with mozzarella cheese and spicy tomato paste, or if the United Coffee House in New Delhi is famous for its king-size mutton ‘keema samosa’, or if the first Indian chef to earn a Michelin star, Vineet Bhatia, popularised the ‘chocolate samosa’, they can safely say they are treading on the path laid out by the creative cooks of the age of ‘Nimatnamah’ and the ‘Ain-i-Akbari’.

The ‘shingaras’ of West Bengal come loaded with potatoes with skin on, cauliflower florets and peas, and Hyderabad’s ‘lukmi’ has a thicker crust and mutton mince filling. The ‘samosa chaat’ has become a hugely popular variant of the more common ‘bhalla papri chaat’ – the tasty triangles are crumbled, spiced ‘chhole’ (chickpeas) are added, and the combination is doused with coriander-mint and tamarind chutneys. In school and college cafeterias, a samosa crumbled and drizzled with tomato ketchup is packed between two slices of regular white bread, giving birth to a delicacy that has been known to generations as the ‘samosa sandwich’. And in Jhansi, samosa is eaten in the Bundelkhandi style with a splash of ‘kadhi’ and topped up with condiments.

Talking about the myriad ways in which the samosa has been served and reinvented over the ages, one cannot but mention the twist that Bihar’s popular political leader Lalu Prasad Yadav’s supporters gave to the song picturised on Akshay Kumar and Juhi Chawla. “Jab tak samose mein rahega alu,” they chanted, “tab tak rahega Bihar mein Lalu.” Yadav, though much loved in his home state, has had a roller-coaster ride of a career after this slogan was coined, but the samosa has seen no diminution in its universal appeal: it continues to rule our tea-time, alu or no alu.