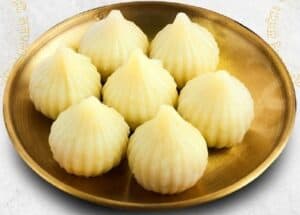

It is Ganesh Chaturthi and time for all of us to gorge on modaks, the sweet conical dumplings synonymous with our favourite Elephant-Headed God, who is also known as Lambodara because of his potbelly, a sign of his abiding love for good food.

Devdutt Pattanaik, India’s premier mythologist, highlights the symbolism of the dumpling, which is most commonly steamed and filled with a paste of jaggery, desiccated coconut and sesame seeds. In his slim but information-packed book, ‘99 Thoughts on Ganesha’, Pattanaik points out that a modak is shaped in the form of a pouch-like bag of money, similar to the one carried by Kuber, the treasurer of the gods. It is therefore “a symbol of wealth, and all the sweet pleasures that wealth can bring to man.” The root of ‘modak’ is the Sanskrit word for happiness or bliss, namely, ‘moda’, which also appears in ‘pramoda’.

Kuber, ironically, had once invited Lord Ganesha, when he was a child, to a feast so that he could flaunt his limitless wealth. He lived to regret the invitation because Lambodara, true to his name, had an enormous appetite and just wouldn’t stop eating – he ate the food prepared for all the guests who had been invited and then started devouring everything around him, including Kuber’s glittering jewel-studded palace.

Not finding anything more to eat, he threatened to gobble up Kuber, who panicked and went to Lord Shiva to save him. Lord Shiva then taught the vain Kuber, who loved to show off, that just a handful of roasted rice was enough to satiate his son as long as it was served with humility and love. Kuber did exactly that and Lord Ganesha couldn’t have been more satisfied. Moral of the story: With wealth must come humility.

Pattanaik notes that the modak is shaped like a triangle pointing upward, which, in Tantrik art, represents spiritual reality. It has therefore “the aesthetics and flavour of material reality but the geometry of spiritual reality”. This one is clearly not an ordinary sweetmeat. Even the number of modaks served to the Lord – 21 – is based on Samkhya philosophy, says the web magazine ‘Local Samosa’.

The number 21, according to this ancient school of Hindu thought associated with the Vedic sage Kapila, is obtained after adding up the five ‘karma indriyas’ (work organs), five ‘gyan indriyas’ (sensory organs), five ‘tatvas’ (elements that make up the Earth), five ‘tanmatras’ (sensory perceptions) and the singular ‘man’ (mind). The 21 modaks therefore represent the ultimate offering that a devotee can make (his or her entire being) to realise the greatness of God.

Then we have wonderful stories woven around the modaks. Lord Ganesha, according to the Brahmanda Purana, had a showdown with Parashurama, the sixth avatara of Lord Vishnu, who attacked him with an axe gifted to him by Lord Shiva. As a mark of respect for the fact that the axe was Lord Shiva’s gift, Lord Ganesha did not resist and in the bargain he broke one of his tusks. As a result of his broken tusk, writes Himanshu Bhatt in ‘Local Samosa’, he was not able to eat much except soft modakas, slathered with ghee, which did not require to be chewed much and yet were fulfilling. This is how modaks became Lord Ganesha’s favourite.

Then there’s the story, also recounted in ‘Local Samosa’, about Lord Shiva, Goddess Parvati and Bal Ganesha visiting Anasuya, an ardent devotee and a godly woman, at her home on the edge of the Chitrakoot forest. When they were seated for the meal, Anasuya insisted on feeding Bal Ganesha first and only after he was satisfied were Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati to be served. True to his form, Bal Ganesha refused to stop eating till Anasuya fed him a modak.

The moment Bal Ganesha ate it, he let out a burp of satisfaction, and Lord Shiva burped 21 times, saying he felt full although he had not eaten anything. Taking the cue from Anasuya, Goddess Parvati served her little one modaks with every meal.

Modaks are now associated mainly with Maharashtra – as is Ganesh Chaturthi, which was turned into a mass festival (Ganeshotsav) during the freedom struggle by the nationalist leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak – but the earliest references to them come from Sangam literature, composed in the second century BCE in present-day Tamil Nadu. Noted food historian K.T. Achaya mentions references in Sangam poetry to rice dumplings with sweet stuffing being sold on the streets of the temple town of Madurai.

‘Manasollasa’, an early 12th-century culinary treatise composed in Sanskrit by the Kalyani Chalukya King Someshvara III, who ruled over present-day Karnataka, also describes modaks as being prepared with rice flour and a sweet stuffing spiced up with cardamom and camphor. The treatise has another name for modaks, namely, ‘varsopalagolakas’, an allusion to their resemblance to hailstones.

In an article carried by ‘Down to Earth’, Rajat Ghai quotes the well-known food writer, Vikram Doctor, as saying that ‘Samaithu Par’, the Bible of Tamil Brahmin cooking by S. Meenakshi Ammal, lists “four types of modaks to be made, separately stuffed with sweet mixtures of coconut, ‘urad dal’, sesame seeds and ‘masoor dal’. These are to be served with raw rice idlis, ‘vadai’, ‘payasam’ and ‘maha neivedhyam’, which is rice with ghee poured on top.” Modaks are either steamed (‘ukadiche’, made with rice flour) or fried (‘talalele’ or ‘talneeche’, prepared with wheat flour dough).

Doctor also notes that Lord Ganesha is worshipped with as much ardour in the South – mainly in Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, where the god is known as Vinayagar and Pillaiyar – as in Maharashtra, where he was first worshipped in the 12th century in and around modern-day Pune, but never became the principal deity till the rise of the Peshwas.

It is most likely, says Saili Palande Datar, an independent art historian and archaeologist quoted in the ‘Down to Earth’ article, that the tradition of serving modaks to Lord Ganesha travelled to Maharashtra from Thanjavur, the temple town that Chhatrapati Maharaj Shivaji conquered and the Marathas ruled from 1674 to 1855. The Thanjavur Maratha rulers, in fact, were known for their love for food and it was during the reign of Serfoji II, one of the dynasty’s later rulers, that the oft-quoted classical cookbook ‘Sarabendra Pakashastra’ was complied. The modak, clearly, is not just another sweetmeat. It is steeped in history and mythology, which means each bite you take is like a story unfolding on your tongue.

Do you feel like celebrating Ganesh Chaturthi with chocolate modaks prepared by Chef Ayushi, or Chef Ankur’s ‘ukadiche’ (steamed) modaks, or perhaps modaks with besan, khoya and coconut by Chef Sarika? Log on to www.wethechefs.in or call +91 88009 88490

Loved reading this Sourish and had no clue that there was history behind the delicious Modak.

Wow. Did not know about the legend behind the humble and much loved modak. It’s a work of culinary art which should be celebrated and made as famous as the xia lao bao. What’s extraordinary is that they are best made at home. An example of culinary skills that exist in kitchens across India and which have been passed down across generations. Thanks for sharing the backstory.